If China can’t get American tech, maybe US allies will be more open to supplying chips

- Industrial powerhouses such as Germany or the Netherlands might be less inclined to ‘blindly follow the United States’ amid growing calls for cautious policies on China

- Turning unilateral export controls on China into multilateral controls looks to be a major challenge and a ‘key White House diplomatic priority’

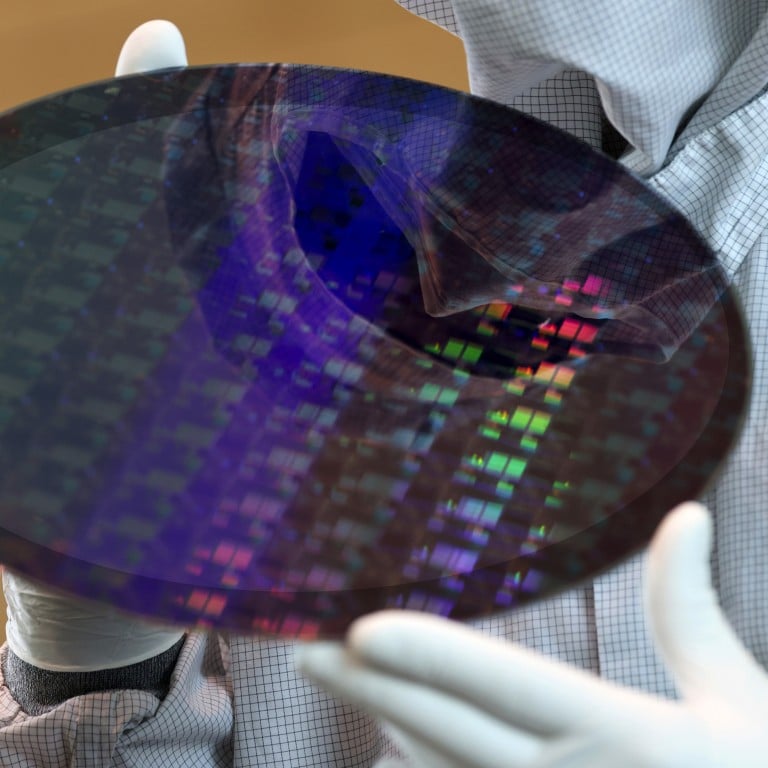

With the US ban on critical computer chips threatening to derail China’s development in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and supercomputers, analysts say that enhancing coordination with American allies could prove decisive for Beijing.

Electric vehicle batteries, artificial intelligence systems and the IT industry are widely expected to be affected, as export controls on semiconductors will send shock waves through other industries that also rely on chips in their end-product, or downstream in their production chain.

“Whether and to what extent US allies and partners join the ban will have a bearing on the impact of this recent policy,” said Andrew Yeo, a senior fellow and the SK-Korea Foundation Chair in Korea Studies at Brookings Institution’s Centre for East Asia Policy Studies.

‘China is under siege’: US tech controls set stage for ‘aggressive’ response

Gregory C. Allen, director of the artificial intelligence governance project and a senior fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said the US needs to make sure that all of its allies are “rowing in the same direction when it comes to keeping China’s semiconductor industry down”.

“Turning these unilateral export controls into multilateral ones will be a major challenge. Expect this to be a key White House diplomatic priority for discussions with Europe, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea going forward,” Allen said in a blog post earlier this month.

Besides the US, China has relied on imported advanced chips and related equipment from Japan, South Korea and Europe, as it cannot yet manufacture them on its own.

Chung Min Lee, senior fellow with the Carnegie Asia Programme, said that there are immense challenges in forging a consensus within the Western bloc on formulating a new China strategy, because America’s allies and partners all have significant economic ties with China.

“South Korea will align itself very closely with the United States but will step back from blindly following the United States as its competition with China intensifies,” Lee said.

Industrial powerhouses … will find it harder to limit their relationship with China

Taiwan signalled on October 8 that Taiwanese companies would comply with the US’ rules, but analysts said this could be a more difficult decision for countries such as Germany.

Countries that traditionally have robust relationships with the US, such as Poland and Lithuania, will be more likely to follow the strategy of containment, said Patryk Szczotka, an associate with the Institute of New Europe.

“Industrial powerhouses – the likes of Germany or the Netherlands – will find it harder to limit their relationship with China, even though political calls for more cautious foreign policy towards Beijing are growing louder,” Szczotka said.

However, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there have been growing concerns in the European Union over its reliance on Chinese rare earth metals, and such worries are compounded by China’s domination in the production and processing of rare earths – essential elements that are widely used in all types of advanced electronics.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, has said that the European Union cannot become as dependent on Chinese rare earth metals as it has been on Russian fossil fuels.

EU to tackle China’s dominance of minerals to avoid ‘mistakes of the past’

“We have been so reliant on certain critical parts of the trade relations with China, it’s just difficult to upend that,” said Nis Grunberg, lead analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies.

In the end, the US’ restrictions on semiconductors exports could dampen China’s integration in the global supply chain, leaving it with few options other than building its own system, said analysts. China is also likely to leverage its trade relations with individual countries and companies in persuading them to not join the US in implementing such debilitating export controls.

China is already investing heavily in its own capabilities to become more self-sufficient. Market intelligence firm IDC predicted that China’s artificial intelligence investment could reach US$26.69 billion in 2026 and account for about 8.9 per cent of global investment, which would put it at No 1 in the Asia-Pacific region, ahead of Australia.

The critical question for many foreign business will be whether they can afford not to follow US’s export controls, according to Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief economist for the Asia-Pacific region at Natixis. “If you do not follow, you may be subject to same export control,” she said.

While China’s state-led effort to move up the semiconductor ladder chain has yet to bear fruit, it is quietly gaining ground in sub-sectors of the chip industry, even though its overall market share and profitability are still low, according to research by Natixis. China’s global share of fabrication capacity also grew from 20 per cent in 2019 to 24 per cent in 2021, but it would be 15 per cent if foreign firms in China are excluded, Natixis said.

It said that a full-fledged chip ban, including the matured processes, would deal a severe blow to the Chinese economy and global supply chain. “It is unlikely, though, given high global inflationary pressure, and the cost is too high for the US,” the French investment bank said.

“For China, the government will certainly react by stepping up financial support for indigenous innovation, and by acquiring foreign semiconductor firms, which may heat up the protectionism sentiment and investment screening in the global political climate,” it said.